One of the first

serious works about Stonehenge was written by Geoffrey of Monmouth in 1135 and

had the name "Historiae Regum Brittaniae", the History of English

Kings.

In this worthless

but puzzling book states Stonehenge would have been built in charge of the

British king Vortigern as a monument for 460 killed knights, all died in a

battle close to the site, about 490 BC.

It could be

Geoffrey misled himself by exchanging Amesbury Abbey or Avebury with

Stonehenge, a likely mistake because these places are very close to each other.

The story tells us

how Vortigern visited the dead men, thinking how to honour them. The Archbishop

brought the solution, by pointing to Merlin, saying he would be the perfect man

to do the job. Of Merlin was said he was a truthseeing prophet with knowledge

of technical matters. Later this reference to prophecy would lead to

astro-archeology nowadays.

Merlin was led

before the king and he presented a plan for a monument fit for the kings'

purpose: the "Giants Ring" in Kildare, Ireland. This Giants' Ring

should be moved and re-erected in exactly the same way as it were in Ireland.

If this should be done, the monument would stay forever.

According to many,

however, Henry of Huntington was the first one mentioning Stonehenge in

literature: in his Historia Anglorum (1154) he calls Stonehenge the second

Wonder of Brittania. Henry used, as almost everyone at that time, the

statements and filosophies of Geoffrey of Monmouth.

Latin writers,

like Giraldus Cambrensis (1146-1223) also used Geoffrey of Monmouths version

and changed some small things (G. Cambrensis, Topographica Hibernica, 1187).

For a long time,

Geoffreys story was more or less the basic for all "scientific" works

about Stonehenge. Only two men didn't use his story.

For a long time

rumours were going about the fact the stones couldn't be counted: the counting

of stones placed in a circle appears to have been very difficult. It was said

to be the work of the devil, or the magic powers of Merlin, the guy helt

responsible for the erection.

Finally, in the

second half of the 17th century, two men finally succeeded in counting the

stones: John Evelyn counted 95 stones in 1954 and John Ray counted 94 stones

the 14th of july 1664.

The question of

who built stonehenge and especially why, has led to discussions, fights, weird

theories and targeted investigation for centuries, without ever finding

something really interesting.

Countless

connections have been made between this mysterious group of stones and Romans,

druids, Phoenicians, Danes and even aliens.

|

After the death of Inigo Jones in 1652 his son-in-law John Web published Jones' book "Stone-Heng Restored". Jones had studied the stones fairly thorough, made lots of notices and measured the stones for the first time..

This study resulted in the first serious attempts to solve the mysteries of Stonehenge. He also rejected the ideas of Geoffrey.

He pointed at the fact the Romans left Stonehenge untouched, while they demolished entire holy woods. Jones also said very subtle that Merlin, if the guy ever had existed, had nothing to do with a transport of stones from Africa to Ireland, as Geoffrey had written.

|

About a year after Webb published Jones' book, Thomas Fuller published a book in which he completely enfeebles the Jones' book.

Fuller, too, had no idea of how the stones came on Salisbury Plain.

Walter Charleton thought the theories made up, until then complete nonsense, so he published his book "Chorea Gigantum" in 1663, in which he draws parallels between Stonehenge and other, almost identical sites in Denmark. His conclusion was that the Danes must have build Stonehenge. This is not even a bad theory, because not long ago indications have been found there have been Danes in England at that time.

This theory, together with the assertion Jones' calculations would've been wrong, made John Webb write a book as an answer to Charletons' book.

The book, "A Vindication of Stone-heng Restored", was publis-hed in 1665. In this book Webb had made some minor changes of Jones' version, and he stated Charletons' book was one big fantasy of Charleton.

In 1725 a publicist published the three books in one band, together with some more pictures and drawings (D. Browne 1725).

In the same time John Aubrey had visited Stonehenge and he thought Stonehenge had something to do with the druids. This theory was later to be supported by William Stukeley. These two men both investigated Stonehenge and other monuments in the surroundings very good.

Aubreys naam zal altijd aan het monument verbonden blijven, Aubreys name shall be connected to Stonehenge forever, because he found trails of 56 holes just inside the bank. These holes are named after him: Aubrey Holes. Aubrey thought Stonehenge was not Roman or Danish, had nothing to do with Irish magic, and neither has been a burial ground. Aubrey also discovered the stone circles of Avebury when he was 22.

Stukeley had read, before he had seen Stonehenge, most of the books about Stonehenge and Avebury. He adapted Aubreys theories.

Both gentlemen thought Stonehenge had something to do with druids, who came along with a group of Phoenician colonists.

Using the Druids, Stukeley connected Stonehenge with the Old Testament, especially the part with stone altars... and from there the connection to human and animal offerings was a short step!

Stukeleys interpretations and theories about Stonehenge and Avebrury have had a great influence on the tales and legends of that time.

In 1829 a book from a guy named Godfrey Higgins called "The Celtic Druids" was published. In this book Higgins refers to notes made by Mr. Waltire, a nature philosopher/astronome. This mr. Waltire stated Stonehenge was built for multiple purposes: first, if you stand right in front of the Altar Stone, you could be heard by everyone in the monument. Second, some astronomical observations would have been done. The barrows were to point out the places of certain star groups in this theory. (Higgins 1829, page 18)

Waltire also shows us that some ancient British constructions are higly probable meant to be seen from the air, but made centuries before the first hot-air balloon was airborne.

Dr. Higgins writes on page 158 of his book Stonehenge should be 4000 years old. With this estimate he was closer to reality than others from his time, who all thought Stonehenge was built after Christs death.

In 1846 the book "The Druidical Temples of the Country of Wilts", written by Mr. E. Duke, was published. This man had some exciting ideas: he thought that the Wiltshire Downs, in which Salisbury Hill was situated, were a big planetary. These kinds of thoughts are the basics of Astro-Archeology.

The wildest ideas appeared suddenly, ideas of which a big deal was rejected almost immediately. Both presumptions Stonehenge should be a sun- or a moonsobservatory are from this age and both sound quite logical.

Professor Richard Atkinson did a lot of digging in and round Stonehenge and he, too, discovered a lot of new things. He writes about it in his book "Stonehenge", published in 1956 and which has become a classical part for archeologists.

|

|

If we are talking about a precise observatory for sun and moon cycles, we are talking about Stonehenge Stage I. The stages after this first stage were correct according to measurements, but weren't precise enough by far.

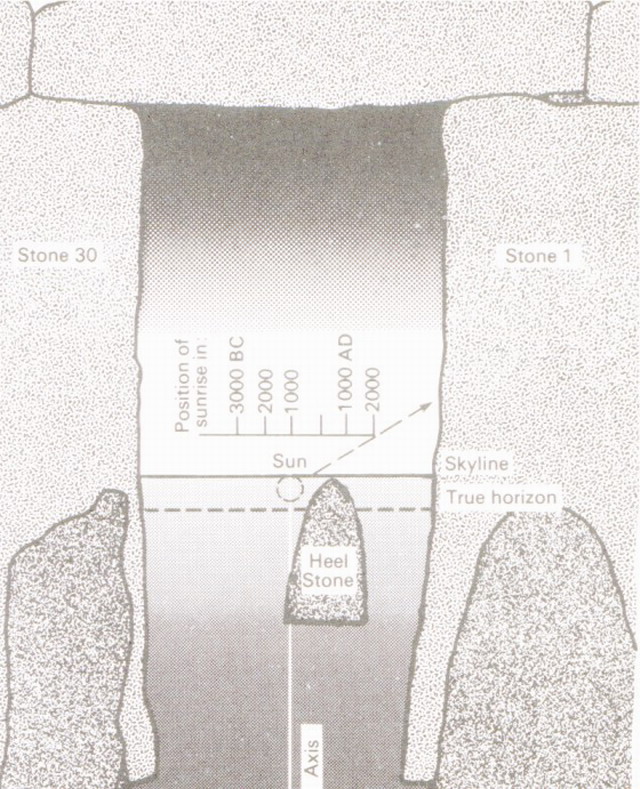

Calculations have proved the sun should have rised over the Heel Stone at Midsummer, if the horizon was built up of trees each 10 metres high.(Atkinson 1978)

Only, the Heel Stone is a very bad indicator for this event, because the stone is far too close to the observer for a precise measurement. The Lane however, on which The Heel Stone is located, runs to the northeast far enough for a precise observation. This makes it almost clear this Lane has been an indicator for midsummer.

An other possible purpose for the Heel Stone is to indicate moonrises in certain periods.

|

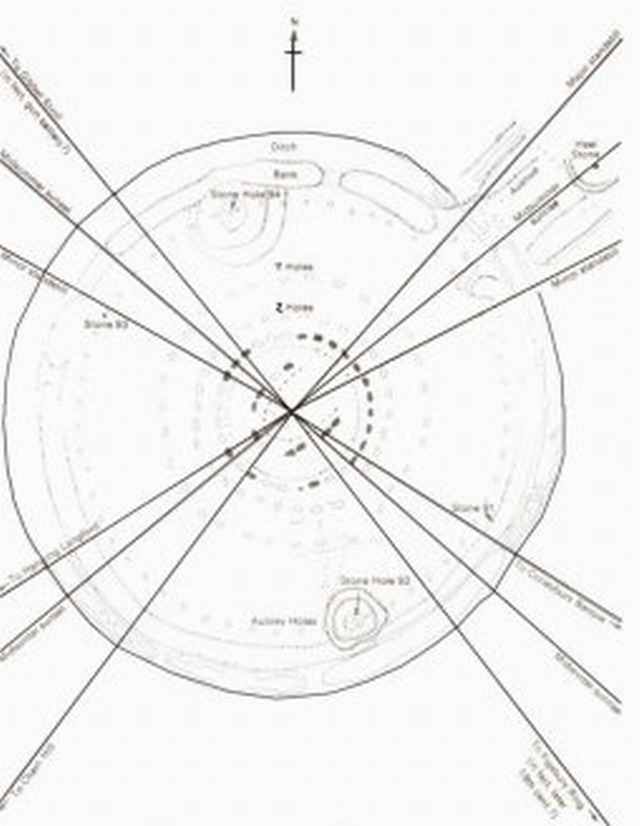

The lines between station stones 91-92 and 93-94 run parallel to the axis of the lane and therefore also parallel on the line between the middle of Stonehenge and the place of sunrise at midsummer. But the Station Stones also do have an other function: seen from the middle of the circle stone 93 indicates the sunset on the 6th of may and august, 8, and stone 91 indicates the same for the 5th of february and the 8th of november. As said, the Heel Stone and the Lane mark midsummer sunrise, and when you extend the line through the middle of the lane southwestward, you'll find the point where the sun sets on midwinter.

This divides the year roughly into 8 months, each of approxi-mately 45 days.

Only the days exactly between midsummer and -winter weren't indicated. A solution was brought by Mr. C.A. Newham, who found the indicator in the line between stone 94 and a hole found together with some other holes close to The Heel Stone in the lane. |

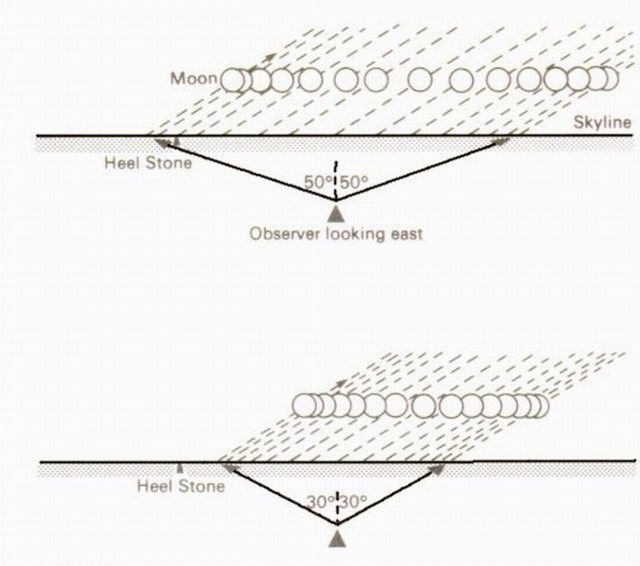

In 1963 the idea roused that Stonehenge could be an observatory for movements of the moon. The movements of the moon are far more complex than those of the sun and that makes it harder to design an observatory for.

The moon follows a rhythm repeating once in 18,61 years. When Dr. Gerald Hawkins let a computer do some calculations on the lines between all stones of Stonehenge, he found some very strong evidence that Stonehenge indicated important points in the mooncycle. He published the results in a scientific magazine (Hawkins 1963).

|

During the 18,61 years of one mooncycle the angle between moonrise or moonset and the line exactly to the east varies between 30 and 50 degrees (see drawing). Newham discovered that the Station Stones mark the extreme moon rises and sets.

Newham also found that the opening between bank and ditch not together with the lane marked the sunrise on midsummer, but marked the sunrise at its most northern point. This is a bit further north than the sunrise. For the rest some holes are found in the entrance, and they must have contained timber. The wooden piles in those holes are presumably set each mid-winternight to mark the rise of the full moon. This made the theory of Stonehenge I was a moonsobservatory even stronger.

|

|

On the left side of the Heel Stone, too, there have been found holes which contained wooden piles, that stood exactly in line with small holes in the covering stones of the Sarsen Circle of Stonehenge III. (Brinckerhoff, 1976)

The deviation between the lines and the most northern moonrise is 0,2 degrees, exactly the deviation the earth made on his axis in the period between when Stonehenge was built and now.

Professor Thom investigated the possibilities of marks on the horizon to indicate important moments in the mooncycle. They thought of hills as a basis for huge timber piles.

Newhams discovery about the perfect rectangle, however, looks much more important. If Stonehenge would have been situated 80 kilometres to the north or south, the deviation in the rec-tangle would already have been 2 degrees and thus form a parallellogram.

If Stonehenge I was a moonsobservatory, it would have been likely that it was built together with other observatories throughout England and developed further because of its special location.

Stonehenge II and III appear to be of less astronomical con-cern, if we keep midsummer sunrise and the holes in the covering stones out of sight.

The discovery of Hawkins that sight-lines between the trilithons and the holes of the Sarsen Stones indicate important moon- and sunrises and -sets is funny, but not precise enough. Someone else said about Stonehenge III that it was a great, but not precise monument of Stonehenge I and possibly also of Stonehenge II. (Gingerich 1957)

Nowadays the question is not anymore if Stonehenge was an observatory, but more if it wasn't also a computer for predic-tions about the sun- and mooneclipses. In 1964 Gerald Hawkins presented a calculation model in an article in the magazine NATURE.

This model, however, was too simple: much of the predicted eclipses couldn't even be sighted from out of Stonehenge and therefore not interesting. Hawkins model only predicted a tiny bit of all eclipses.

Professor Thom found some proof that Scottish Astronomes used marks on the horizon to see little changes in the movements of the moon. If these marks also have been close to Stonehenge, it would have been very good possible that Stonehenge has been the place where it worked successful for the first time, and that the method has been exported to other places.

Man has come this far with the investigations on Stonehenge. The question now is if more discoveries are to be done. I think this will happen.

|